Northern Nevada’s love affair with noodles.

The days are cooling and the image of a steaming bowl of fresh spaghetti calls. The allure of pasta is nothing new — its powerful pull has lured Northern Nevadans for generations. It should come as no surprise that the Italians brought their love of noodles to the region more than 150 years ago. They were drawn by cheap land for farming or ranching, and many came to work on the railroad. By 1910, they were the largest European ethnic group in Nevada.

They called it macaroni

What’s in a name? Lots, when tracing the history of pasta. Although the term pasta wasn’t favored, the words paste, macaroni, or the names of specific pasta shapes (vermicelli, spaghetti, tagliarini) were used, with references back to 1898. When the term pasta appeared, it referred to traditional Italian recipes, as in a headline from 1912 that read, “Pasta Fazool is Popular.”

People either made their own or ordered from regional purveyors. Things changed with local manufacturers such as the Bianchi & Co. Macaroni Factory. A February 1900 Nevada State Journal ad read, “We invite you to place a trial order with us before sending away.” The company produced “macaroni, vermicelli, spaghetti, and all Italian pastes.” Nevadans now had a local source.

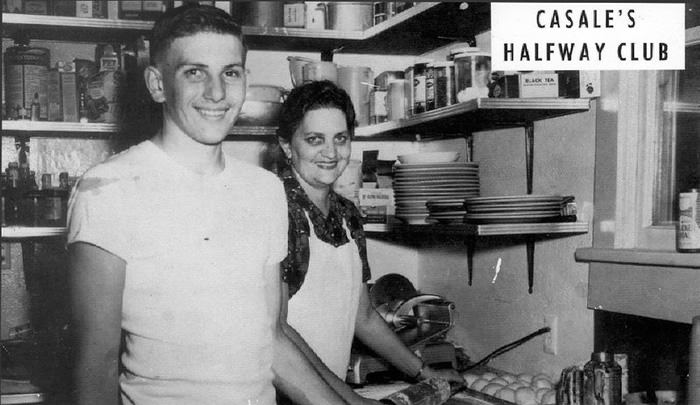

Inez Casale Stempeck and son Charles. Photo courtesy of Sparks Heritage Museum.

Industry flourishes

More local manufacturers followed. In 1901, A.T. Dormio’s newly constructed factory was destroyed by fire. P. Santina left San Francisco after the destruction of his paste factory in the 1906 earthquake, took his insurance money, and invested in a plant in Sparks. One of the most publicized businesses was the Purity Bakery and Macaroni Factory, described in a Nevada State Journal story in 1919 as “the only macaroni factory in Nevada,” touting its “splendid consuming territory.” By 1924, nationally manufactured pastas were available in grocery stores, bringing local manufacturing to a close.

Ravioli also moved into commercial production. An ad for the Reno Ravioli Factory, owned by Lorenzo Zunini & Son, ran in the Reno Evening Gazette in 1921 announcing, “Ravioli, Noodles, Tagliarini made fresh every day in a sanitary kitchen — inspection invited.” When Lorenzo died in 1929, his two girls (the Zunini sisters) took over what was called the oldest ravioli factory in Nevada.

Pasta emerged from home kitchens around the 1920s, and restaurants featured it proudly. The Mizpah Hotel in Tonopah, like so many, offered ravioli, spaghetti, or noodles “at any time, we cook any style.” Most dinners cost around $1. Spaghetti feeds were described as early as 1926 when George Lott hosted visiting racers from the Reno Motor Speedway. Sometimes the spaghetti was topped by strange (to today’s tastes) sauces such as mushroom gravy, or served au gratin style.

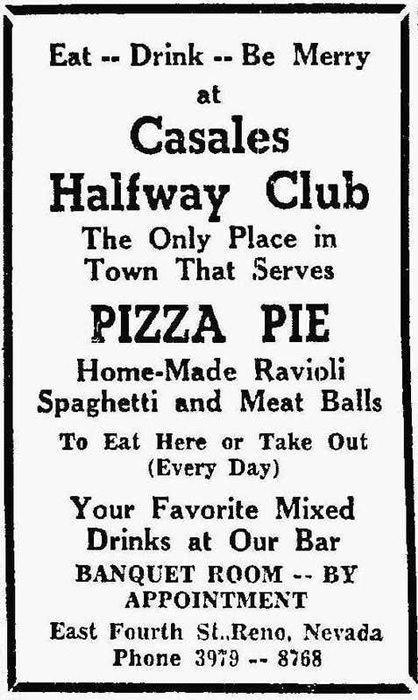

Casale’s ad

Casale’s Halfway Club outlasts them all

One restaurant is the longtime champ in serving pasta: Casale’s Halfway Club. It sits on the old Lincoln Highway (now Fourth Street) halfway between Sparks and Reno. It’s touted as the oldest, continuously family-owned and operated restaurant in Reno (and possibly in the entire state). It might be better called a family joint, filled with old timers and a legion of younger generations.

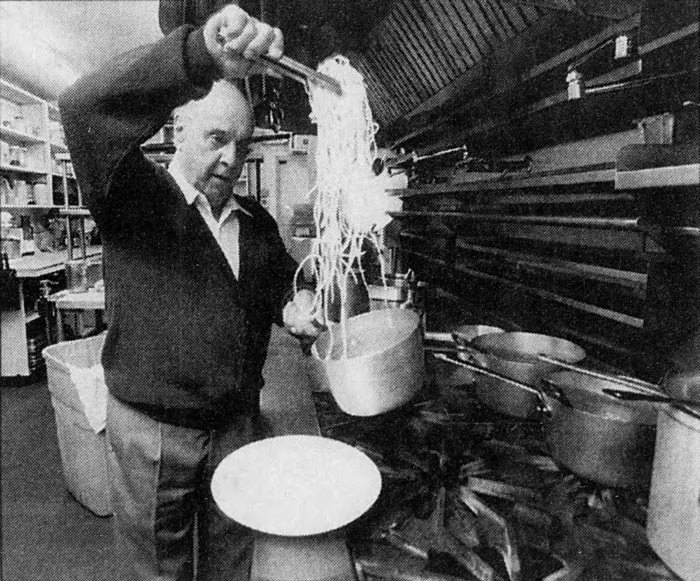

It all started when Italian natives John and Elvira Casale opened a produce stand in the late 1930s. It soon expanded, and by 1941, besides fruit, Casale’s Market offered handmade ravioli. By the mid-1940s, the name Casale’s Halfway Club was solidified. Daughter “Mama” Inez married Casimir “Steamboat” Stempeck in 1946, and he became part of the business. The menu continued to expand, from ravioli to spaghetti, pizza, and other Italian specialties. Mama Inez runs it to this day, with her children and, in more recent years, her grandchildren. It still is a family tradition to produce the house-made ravioli that inspires cult-like admiration.

The Italians brought pasta to this region in the earliest days, but Americans are still bush-league consumers of the stuff when compared to Italians. While we twirl 26 pounds annually, diners in Italy top the charts at 60 pounds. So get the water boiling — that’s a lot of catching up to do.

Sharon Honig-Bear was the longtime restaurant writer for the Reno Gazette-Journal. She relishes Reno history and is a tour leader with Historic Reno Preservation Society. You can reach her with comments and story suggestions at Sharon@ediblerenotahoe.com.