edible traditions

ANCIENT MEDICINAL

Mormon tea offers a living history lesson of Nevada’s high desert.

WRITTEN BY JEN A. HUNTLEY

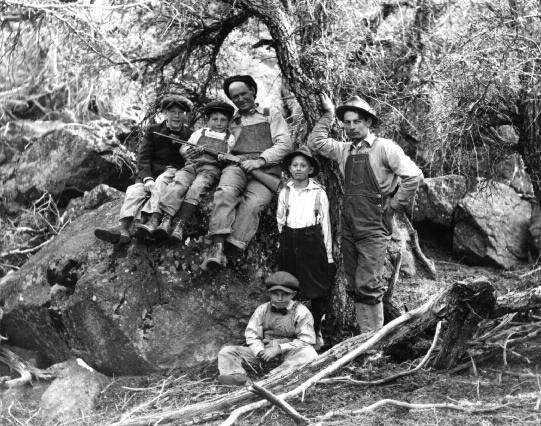

PHOTO COURTESY OF UNIVERSITY DIGITAL CONSERVANCY, THE UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA, RENO

Standing out in the sea of gray-green sage, mountain mahogany, and pinyon pines, the bright green spines of Nevada’s Green Ephedra shrubs announce their unique role in the ecosystem and human history of the Great Basin. Although shrubby in stature, the plant is more closely related to cone-bearing pines and firs than to flowering plants. A characteristic component of the Great Basin’s pinyon-juniper woodland ecosystems, Ephedra viridis and its lower-elevation cousin Ephedra nevadensis provide habitat and food for desert-dwelling birds and squirrels; throughout the Great Basin’s history of humans, the plants also have seen widespread use among both native and European immigrant residents.

Commonly known as “Mormon Tea,” Ephedra performed different medicinal functions for the Sierra Nevada Miwok, Kawaiisu, Paiute, and Shoshone peoples. Native residents of the Great Basin used Green Ephedra for maladies as diverse as blood thinning, respiratory complaints, backache, and irregular kidneys. Frequently, the plant’s stems and spiny leaves were steeped in a tea, but they could also be dried and pounded into a flour, or made into a poultice. A biological cousin of the Ma Huang, or Chinese Ephedra that recently gained notoriety for its misuse as a weight-loss supplement, Green Ephedra contains pseudoephedrine and is federally recognized as a toxin. Foragers should never attempt to consume wild plants without the direct oversight of a botanical expert.

With the arrival of Euro-Americans into the Great Basin, pioneers adopted Green Ephedra from the Amerindians. Mormon settlers, banned from consuming black tea or coffee, decocted the plant into the mildly stimulating beverage that gives the plant its common name. Additional English names point to other uses the pioneers found for the medicinal: “Desert tea” or “cowboy tea” suggests the way Euro-American herders could draw resources from the environment in their long stints in the backcountry. Perhaps the most colorful name, “whorehouse tea,” refers to rumors that strong decoctions of the herb could cure syphilis, though there is no independent scientific confirmation of this rumor.

This ancient healing plant now enjoys another role in its evolving relationship with humans: as a key ecological and habitat restoration plant in desert areas disturbed by fire, overgrazing, or off-road vehicles. Like so many of its Great Basin neighbors, Green Ephedra illustrates the resilience and adaptability of living organisms to the high desert ecosystem.

Jen A. Huntley is professor of humanities at Truckee Meadows Community College in Reno, and author of The Making of Yosemite: James Mason Hutchings and the Origin of America’s Most Popular National Park.