edible traditions

DISTINCTIVE DISHES

Four tasty tidbits from our culinary heritage.

WRITTEN BY ALICIA BARBER

PHOTOS COURTESY OF SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA,

RENO LIBRARY AND NEVADA STATE MUSEUM, BOHALL COLLECTION

The commemoration of Nevada’s sesquicentennial this October offers an excellent opportunity to celebrate the state’s unique heritage, including all things culinary. And yet identifying a representative state food is no easy task. Think Wisconsin and immediately cheese comes to mind. Maine summons images of lobster. But Nevada? The question may prompt a blank stare.

There’s good reason for the difficulty. For 150 years, Nevada has attracted people of such diverse cultures and backgrounds that no single cuisine has ever dominated its culinary landscape. Populations shuffle in and out, new arrivals hold fast to long-held traditions, farmers continuously experiment with new crops, and chefs have long catered to tourists from across the globe.

The Reno-Tahoe area alone abounds with countless traditions of food and drink, each one born of a specific time, place, or community, together revealing the richness of our communal heritage. Consider these four examples just a sample platter of what the region has to offer:

Nut of the pines

A native food in all senses of the word, the pine nut has been a dietary staple of the Washoe, Paiute, and Shoshone tribes for thousands of years. It is the treasure at the heart of the pinyon pines that thrive throughout the Toiyabe National Forest of Central Nevada and the Pine Nut Mountains east of the Carson Valley.

Harvested in the fall, the nuts are pounded out of their prickly cones, then heated and shelled to reveal the protein-rich meat inside. Traditionally, Washoe tribe members ground them to make a nourishing winter soup, but by the 1880s, they were also preparing them for shipment to eager consumers in San Francisco and elsewhere.

Roasted and salted, the savory treat was big business by the 1930s, sold locally by the pound and exported across the country as a Nevada delicacy. Several hundred tons of nuts were harvested from Nevada pinyon each year. Demand soared in the 1950s as American housewives experimented with foreign cuisines, topping fish filets with pine nuts browned in butter, or stirring them into cooked rice to serve alongside lamb kebabs. The nut’s popularity has only increased since then.

Cornish pastries

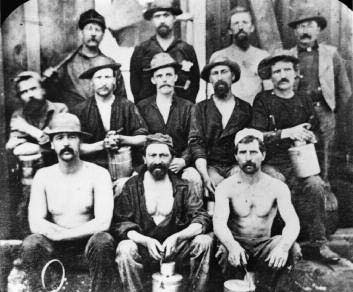

Proof positive that pastry is not for sissies, the Cornish pasty (pronounced past-ē) takes its name from the county of Cornwall, in westernmost England. Hard-rock miners from the region began immigrating to the United States in the mid-1800s, bringing their professional expertise — and their appetites — to mining communities from Michigan to California. By 1870, more than a thousand Cornish, popularly known as Cousin Jacks, found high-paying jobs on the Comstock.

Their namesake dish consisted of a folded pastry crust generally filled with seasoned beef, onions, potatoes, and swede, or yellow turnip. As practical as it was nourishing, the baked D-shaped pasty was easily transported underground for the midday meal in a lunch pail divided into three vertical compartments with a metal cup affixed to the top. The bottom level held coffee or tea, with the pasty placed in the next section, capped by a slice of cake or pie. A miner could easily hold the pie with one hand, crumbling any remnants on the ground for the fabled Tommyknockers, supernatural elves believed by many Cornish to inhabit the mines.

The Cornish generally moved on to other locales when a mining region went bust, as the Comstock did in the 1880s, but the pasty remains a beloved dish in many communities throughout the Sierra and beyond.

Basque dinners

Basque food is known for its hearty mix of entrées, ranging from seafood and lamb to steak, tongue, and sweetbreads. But it is the Basque approach to dinner, served family style, that elevates its cuisine to a regional tradition.

No mere promotional gimmick, the communal style of service stems from the Basque boardinghouses and hotels, or ostatuak, from which most of Nevada’s Basque restaurants descended. Such institutions were a necessity in the Western U.S., where Basque sheepherders — mostly single men — began to congregate in the mid-19th century.

Basque immigration to Nevada accelerated between 1900 and 1910, centering in Elko, Winnemucca, Reno, and Minden-Gardnerville. There, the ostatuak offered the men a sense of community and a taste of home. As the numbers of Basque boardinghouses began to decline in the 1950s, those that survived opened up their rooms and tables to the broader population, which warmed to the congenial style of dining and to the popular apéritif known as picon punch.

All you can eat

No self-respecting Nevada hotel-casino could exist today without an all-you-can-eat buffet. And yet, although Nevada legalized gambling in 1931, most casinos didn’t get into the food business until the late 1940s. After World War II ended, a surge in leisure travel prompted a heightened sense of competition among those hoping to profit from it, and a no-limits buffet was the perfect draw.

Designed to please both palate and pocketbook, many of the first were called chuck wagon buffets and were offered late at night, from just before midnight to the wee hours of the morning. As Reno and Las Vegas vied for the title of Entertainment Capital of the World, their buffets became more elaborate, featuring ice sculptures and prime cuts of beef.

In 1957, Reno’s Riverside Hotel introduced its International Sunday Buffet, with more than 300 dishes from more than 15 countries displayed on a 100-foot-long table, all for the low price of $3 per person. At the more affordable end of the spectrum, Dick Graves’ (later John Ascuaga’s) Nugget in Sparks offered a Friday night all-you-can-eat fish fry for 95 cents per person. Over time, as Nevada’s casinos transitioned into full-service resorts, their buffets became a more standardized and predictable component of the overall experience.

Pine nuts, pasties, Basque dinners, and casino buffets — these are just four of the countless morsels from Reno-Tahoe culinary history. Each dish, like each person, has a story to tell, a story just waiting to be savored and shared so that our collective heritage can remain meaningful, and delectable, for generations to come.

Alicia Barber, Ph.D., is the author of Reno’s Big Gamble and editor of http://www.Renohistorical.org She blogs about history and place at http://www.Aliciambarber.com