Dishing on our region’s popular all-you-can-eat sushi dining.

In The Biggest Little City, a place known for its 24/7, all-you-can-eat options for dining and drinking, most sushi restaurants serve never-ending trays of fish — the options and combinations are boundless. But the ocean’s supply of fish is not.

Roughly one-third of the world’s edible fish populations is caught at faster rates than they can reproduce. But farmed seafood also comes with its own set of environmental and ecological concerns. A constant demand for sushi and a limited supply of healthy, humanely, and holistically procured fish creates a paradox.

“‘All-you-can-eat sushi’ and ‘sustainable seafood’ already sound controversial,” says Tae Sung Lee, owner and executive chef at Tha Joint sushi restaurants in Reno and Sparks.

So can one be compatible with the other? It depends.

“There’s no easy answer; there are a lot of different factors that play into it,” says Jackie Marks, United States senior public relations manager for the Marine Stewardship Council. “I think the answer is yes, it can be, and it requires a very informed consumer, and also a very informed restaurant.”

Why sustainability matters

The seafood in a rainbow roll came to a sushi restaurant’s loading dock via one of two methods: fishing or aquaculture. Both can wreak havoc on the health of the oceans if not practiced carefully.

“One of the hardest places for us to make an impact in the sustainable sourcing of fish and seafood, be it farmed or wild, is in sushi,” says Jennifer Bushman, a food consultant, principal at Route to Market Services, and director of sustainability at Pacific Catch, a California company that sources sustainable fish and seafood.

Industrial fishing, which began in the late 1800s, created insupportable practices resulting in significant declines in the size and abundance of wild-caught fish. Ninety percent of the world’s edible fish populations are now either caught at the same rate as new fish replace them, caught faster than they can be replaced, or almost gone, according to Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch. The program helps consumers and businesses choose seafood that’s fished or farmed in ways that support healthy oceans.

“The oceans were never set up to have the kind of commodity harvest that we now put it through,” Bushman says.

To mitigate impact on the oceans, some companies turned to fish farming, called aquaculture. But farm-raised seafood is not necessarily more sustainable. Fish farming can impact the environment, depending on whether the farm tries to limit the potential damage to the ocean’s ecosystem and economy, and the makeup of nearby communities.

“If you think about farmed seafood, you’re really thinking about all the food and the resources that go into producing one pound of whatever that product might be,” Marks says.

The sustainable seafood movement seeks to address the issues with both caught and farmed practices by promoting the long-term vitality of the species, the well-being of the oceans, and the livelihood of nearby and economically dependent communities. One of the movement’s tenets is deceptively simple: Know where your seafood comes from.

“Seafood is the most traded global commodity,” says Ryan Bigelow, a senior program manager at Seafood Watch. “And it is a dark and cryptic world where not a lot is known.”

Seafood supply chain

Unlike a piece of regionally raised beef that starts on a nearby ranch and ends up on your plate, a fish’s journey from the other side of the globe to your chopsticks can be more complex. While providing seafood for restaurants in a landlocked area, Reno’s distributors trace and document seafood in order to choose the best option, thereby playing an essential role in ensuring the transparency of the area’s seafood options.

“They’re the ones closest to the product; they know what the different options are and what’s in season,” Marks says. “A distributor can really make sure that they know what they’re providing, and they can provide that information to the restaurant.”

One of Reno-Tahoe’s major distributors is Sierra Meat & Seafood, which sells seafood to about 35 or 40 of the region’s 50 or more sushi restaurants.

“We try to buy the best possible fish for a good price,” says Miyuki Wong, the head of the sushi department at Sierra Meat & Seafood, which has been selling seafood in Reno for 21 years. “We definitely don’t just get the cheapest, worst quality, and poorly fished.”

The five most popular types of seafood sold to sushi restaurants in the Reno-Tahoe area are salmon, tuna, hamachi, scallops, and shrimp. Altogether, Sierra Meat & Seafood sells more than 80,000 pounds of these per month.

When procuring these and other items, managers at Sierra Meat & Seafood try to buy as many responsibly produced products as possible. The company is one of four Marine Stewardship Council-certified distributors in the Reno-Tahoe area and meets the organization’s standards for sustainably managed and traceable, wild-caught seafood. Sierra Meat & Seafood managers also purchase farmed seafood that is certified by the Aquaculture Stewardship Council and Better Aquaculture Practices.

“We are conscientious,” Wong says. “We do watch all the things about sustainability and talk about it. We do the best we can. It’s a balancing act. We run a business and yet we try to make good decisions in what we buy.”

Some sushi restaurant owners rely on that mindset and the company’s standards and certifications, says Chris Thompson, owner of Sushi Pier in Midtown Reno, a restaurant consultant, and Le Cordon Bleu graduate.

“We depend on (the distributor) to source a lot of this for us because our location geographically does not allow us to go down to the fresh fish market every day and talk to individual fishermen,” Thompson says. “We have to rely on shipping these products to us over the mountain on a daily basis.”

Buying seafood wisely is partly the responsibility of the distributor and the restaurateur.

“You really need to know what you’re buying,” Bigelow says. “You need to ask those questions, and you need to be willing to have conversations with the people who supply your fish.”

Unlimited sushi?

Every sushi restaurant in Reno-Sparks offers all-you-can-eat sushi.

“I think it’s unique,” says Terry Lee, owner of Sakana Sushi, which has two locations in Reno and a café in the Tesla Gigafactory in east Sparks. “Pretty much wherever I go, there’s not as many all-you-can-eat sushi restaurants compared to Reno.”

The region’s obsession with unlimited sushi began in the late 1990s. Its proliferation in Reno mirrors what happened when sushi first arrived in Los Angeles in the 1980s, says Trevor Corson, a journalist and the author of The Story of Sushi.

Now, it’s practically impossible to operate a sushi restaurant on the valley floor that doesn’t offer all you can eat, Wong says.

“If you don’t do all-you-can-eat sushi in Reno, you won’t make it,” Thompson agrees.

Meanwhile, the environment is different at Lake Tahoe, where, of eight sushi restaurants, only one, in Kings Beach, offers all you can eat, while the rest are à la carte. At Drunken Monkey in Truckee, head chef Rob Watts says that customers will ask why it isn’t an option.

“We do get that question a lot,” Watts says. “Since day one with Drunken Monkey, all you can eat was not the intended style of restaurant. We have such an expanded menu, and 99 percent of our ingredients are handmade. We try to limit processed foods that come into the restaurant. It just wouldn’t be feasible with how we prepare our food.”

Avoiding all-you-can-eat offerings allows Watts to consider seafood sustainability at the restaurant more carefully, he says.

“I’m in direct contact with our purveyors as to where our fish comes from,” he says. “Are they farmed? Are they wild? Then we base our decisions off that.”

That same conscientiousness about seafood sourcing isn’t absent from all-you-can-eat restaurants.

“We check whether the fish is wild caught or farm raised,” Terry Lee says.

Thompson, Terry Lee, and Tae Sung Lee all say they know where the major types of fish served at their restaurants come from and whether they were responsibly sourced — a factor they each consider when running their restaurants. Often, price dictates a choice, especially in the case of bluefin tuna and other high-end fish. As a result, all three owners say much of the seafood that comes into Sushi Pier Midtown, Sakana, and Tha Joint is farm raised and often from suppliers committed to sustainability.

All three also say they must balance their concern for sustainability with customer demand.

“I will probably put my effort to find whichever fish that this market wants,” Tae Sung Lee says. “Basically, I’m delivering sustainable fish or not, whichever our customer wants.”

Keeping customers happy also plays a key role in how each restaurant handles the issue of excess ordering and waste. Sushi Pier Midtown, Sakana, and Tha Joint all similarly treat diners who order excessive amounts of sushi: The kitchen staffs will split those orders and bring them out in stages to minimize waste.

“This is all you can eat, not all you can waste,” Thompson says.

When there are leftovers, all three restaurants charge in some way for takeout boxes. But the goal is to avoid having excess in the first place. Education for both restaurant owners and customers is critical.

“We normally educate people, not just try to charge them,” Terry Lee says. “They will get mad if we charge it anyway. Instead, we try to educate them that it’s wasting for both ends.”

Is the customer always right?

Do the customers ordering all-you-can-eat sushi care about its sustainability? Thompson, Terry Lee, and Tae Sung Lee say it’s a question that they sometimes get asked.

Customers are more knowledgeable about and interested in sustainability, according to the National Restaurant Association’s What’s Hot 2018 Culinary Forecast. The association’s 2018 Top 10 trends included environmental sustainability and locally sourced seafood.

The Marine Stewardship Council found that of the nearly 20,000 North American consumers it surveyed, 49 percent were concerned about overfishing.

That awareness and demand have the potential to shape the future of sushi.

“It really does come back to the informed consumer,” Marks says. “The more they know, the more they’re aware. The more they’re asking the restaurants that they visit for sustainable seafood, the more the restaurants will source it.”

As for offering responsibly sourced seafood at affordable, all-you-can-eat prices, Bushman says it’s possible.

“It’s not that less expensive sustainable fish isn’t available. It is,” Bushman says. “But you have to be an active buyer with an active distributor.”

“Sustainable seafood doesn’t necessarily have to cost more,” Bigelow agrees. “Some of the most unsustainable seafood tends to be the most expensive.”

Offering sustainably raised sushi may also be a matter of preparation and technique.

“I’m not advocating for more expensive, fancy sushi,” Corson says. “I’m advocating for sushi that’s more eco-friendly, healthier for your body, and more sustainable. It can be done by tapping into a lot of Japanese traditional cuisine knowledge. A lot of interesting things could happen there. And it would be fun to eat.”

Annie Flanzraich is a freelance writer and editor based in Reno. While writing this article, she avoided eating rice and soy products as part of Whole30. Now, she really wants a sustainable piece of sushi — or 10.

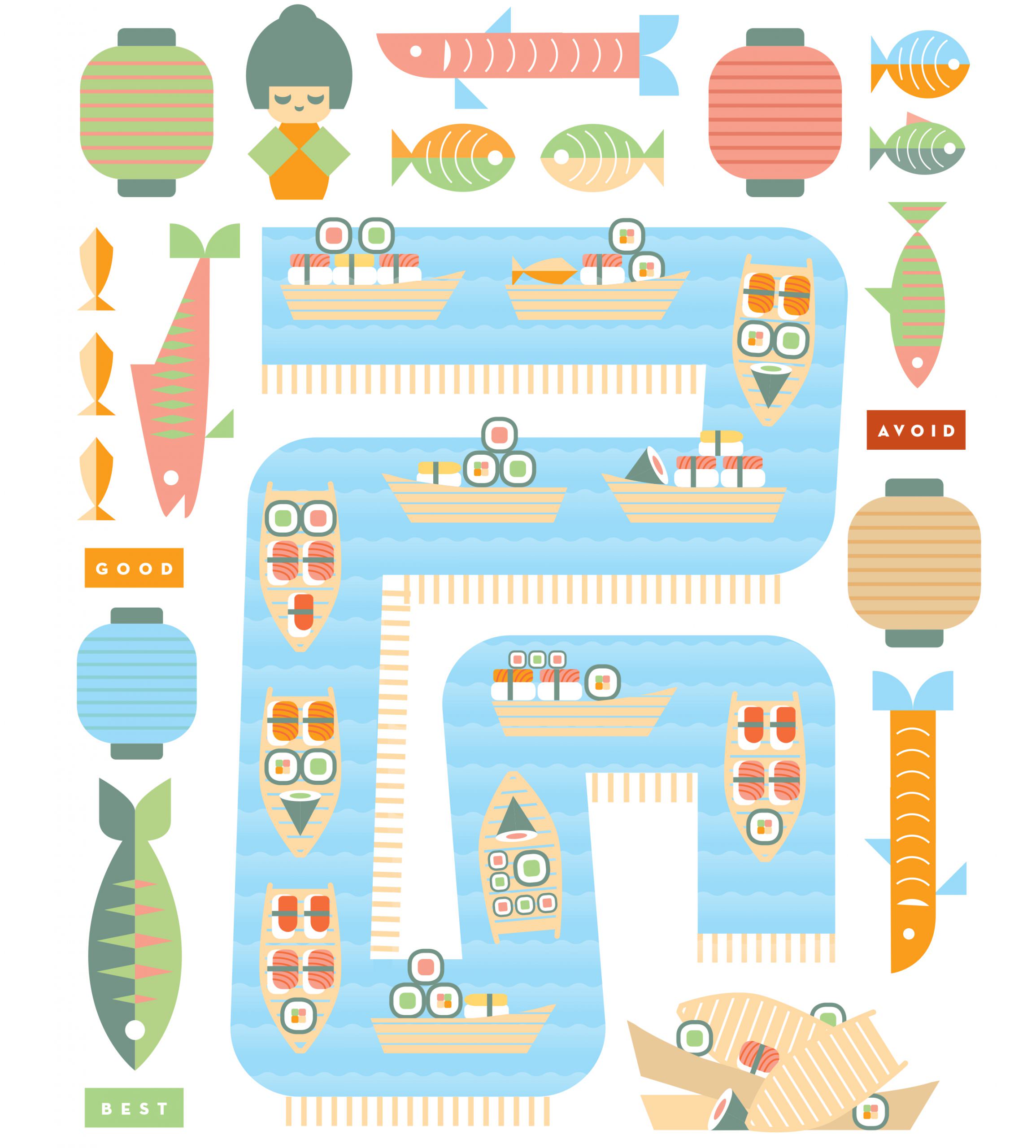

How to make sustainable seafood choices

Creating a sustainable sushi environment is the joint responsibility of distributors, restaurants, and consumers.

“I think sustainability definitely needs to be an important conversation throughout the supply chain, not just at the end consumer,” says Jackie Marks, U.S. senior public relations manager for the Marine Stewardship Council. “It’s a virtuous cycle where, on the one hand, we have the suppliers who are pushing more sustainable products, and then, on the other hand, you have the consumers who are asking for more sustainable products.”

Because of the myriad permutations that go into determining whether a specific fish is sustainable, it’s important to consider each species on a case-by-case basis. That being said, here are some useful guidelines for distributors, restaurateurs, and consumers to consider.

Eat low on the food chain. The larger the fish, the more likely it is to be overfished. On the other hand, bivalves and mollusks often can be sustainably raised and even help the environment when they’re in the water.

Know what you’re buying. Look for certifications from Seafood Watch, the Marine Stewardship Council, the Aquaculture Stewardship Council, and other organizations that establish protocols for sustainability.

Don’t order bluefin tuna. While bluefin tuna is popular, it also is overfished, and populations worldwide are near collapse. Try albacore tuna or shiro maguro instead.

Download the Seafood Watch app. This mobile application from Seafood Watch gives recommendations for seafood and sushi based on sustainability concerns. Users can search for seafood by common market name, or for sushi by Japanese name and common market name; find nearby restaurants and stores that serve ocean-friendly seafood; and access in-depth conservation notes and reports. It’s free to download at Seafoodwatch.org/seafood-recommendations/our-app.