Culinary experts weigh in on the local chefs shortage.

How does a restaurant owner keep creativity thriving while continuing to grow and maintain stability at the same time? The answer is an innovative and reliable chef. Unfortunately, the culinary world, here in Reno-Tahoe and around the country, is facing what some have called a chef crisis.

Skills gap

Finding and keeping qualified workers to fill back-of-the-house positions is difficult, and this may be attributed to a number of causes.

In many cases, chefs are paid little, work long hours, and face a lack of respect, leading to high rates of substance abuse and suicide. A survey conducted by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration in 2015 indicated that the food service and hospitality industry had the highest rates of illicit drug use and substance abuse disorders, and it had the third-highest rate of heavy alcohol use of all industries.

Fred Wright, treasurer of the American Culinary Federation High Sierra Chefs Association (ACFHSCA) based in Sparks and chef-instructor at the Academy of Arts, Careers and Technology’s Culinary and Hospitality Academy in Reno, asserts that the problem is a culinary skills gap.

“Parents want their children to graduate from four-year universities and don’t see the value in trade schools,” Wright says. “If parents and society don’t value a developed skill versus a traditional degree, it’s difficult for today’s workforce to value skill-based work and the time required to develop that talent.”

This societal stigma against skills-based vocations and workforce development is compounded by the fact that in the Reno-Tahoe area, where its food-and-drink industry is rapidly growing, there are more jobs than qualified chefs. Some owners hire exchange students, whom they believe possess a stronger work ethic, or they endeavor to accommodate employees’ needs and whims to keep them happy. Many restaurant owners report being challenged by employees with poor attitude toward work and sense of entitlement, and with the task of keeping chefs from jumping to the next hottest restaurant.

“If I find someone who wants to work and has a desire to learn, it’s golden, but it’s rare,” says chef Shawn Whitney of Morgan’s Lobster Shack in Truckee. “I am honest and expect my employees to show up ready to work, and in exchange I give them time off, even if it means I work twice as hard. Some owners poach employees from competitors by offering as little as 25 cents more an hour, only to fire those same employees when business slows. I offer a year-round wage, despite off-season decline. I want my employees to be happy and successful. I want solutions.”

Mike Rowe, host of TV’s Dirty Jobs and founder of mikeroweWORKS, an organization that supports vocational training to fill in-demand jobs, often speaks publicly about the skills gap dilemma. When it comes to earning high-level culinary jobs, Rowe has advised, “You’ve got to put your skin in the game.” In other words, a trained cook or recent culinary graduate may need to work from the bottom up to develop the expertise and cultivate a well-rounded attitude.

“I’ve hired chefs who went to culinary school and expect high pay but can’t handle a busy line or don’t have the basic people skills to get along with staff or customers,” Whitney says.

“I have met cooks who have worked 10 years and have very few knife skills or basic knowledge of classic French cuisine,” says chef/owner Brett Moseley of Washoe Public House in Reno. “Now, it’s not completely necessary to learn these things, but one would think if you want to be the best at what you do, you would want all the knowledge possible. I have also worked with chefs who never went to school, were completely self-taught, and were great chefs and way more knowledgeable than me. You are only going to get out of it what you put in. If you plan on going to school, you should be ready to give it everything. If you’re going in half assed, then it’s just a waste of money.”

Finding solutions

Local owners use a variety of tactics to develop strong communication and mutual respect to keep chefs engaged and passionate about what they do.

“I fully expect to turn my staff over every year or two,” Moseley says. “One of my mentors once told me that if I worked for a year in five different places, then I’d be fast on my way to becoming a chef.

“When I hire someone I usually ask for a one-year commitment. Anyone can do something for a year, and if for some reason either of us is miserable, then we part ways,” Moseley adds. “I always show them everything I know. I share all my recipes and encourage them to experiment. I show them everything I know about the business side, ordering, inventory, organization, schedule writing, etc. I work side by side with them, wash dishes, and scrub floors with them. I always pull my own weight and show them that we all are a team. I also let them mess up as long as they learn from it.”

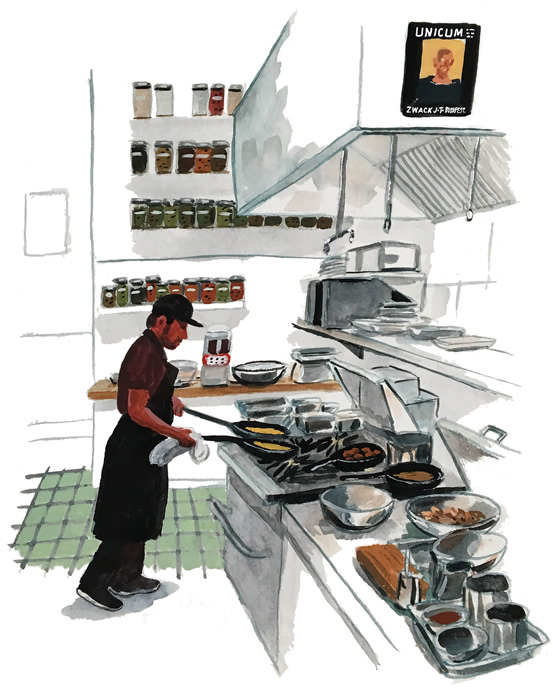

Chef Tony Fish and his wife, Jayme Watts, owners of Sassafras in Carson City, have found longevity with their staff by cultivating a tightly knit family unit. Fish works double shifts in the back while Jayme helps the front of the house run smoothly.

“Tony created an eclectic menu that allows him to play and put his signature twist on his dishes,” Watts says. “He works with our chefs by explaining his concepts and ideas and allows them to grow as long as they want to learn.”

The owners of Great Full Gardens in Reno, Gino and Juli Scala, and their partner, Cyndi Wallis, have created a cohesive team and attracted chefs based on a shared vision: connecting people through food. They source locally and take their staff members on farm tours and team bonding adventures.

“Our leads and managers attend personal development training, so we can easily convey our values and develop mutual respect and appreciation,” Wallis says.

Making the same investment in employees that owners want to see reciprocated in their businesses is the key to success.

“Too many owners don’t invest enough back into the kitchen,” Moseley says. “They spend it on the dining room, which I get, but if you don’t balance it, the back of the house suffers, and the biggest reason that people go to a restaurant is to eat! So why not make sure that the people cooking the food are set up for success?

“Don’t be afraid to let your chef have their own style and vision,” Moseley adds. “The worst thing you can do is shut down all creativity. Keep them in the loop on why you’re making certain decisions … Encourage and even pay for your chefs and cooks to go somewhere and learn. I guarantee they will come back inspired and refreshed, and the food will be better.”

Chefs and owners clearly have a tough row to hoe, and it’s going to take meeting in the middle to continue to bring creativity to the table.

“Culinary training programs around the community are determined to find solutions to fill the gap,” Wright says. “We hope ACFHSCA scholarships and networking opportunities will motivate chefs of all levels to hone their professional skills and provide the quality chefs that our community desires.”

To weather the storm, Moseley offers this sage advice: “Passion is probably the best answer. You have to be very passionate to be successful in this line of work.”

Jamie Della is the author of eight books and several published articles and essays, and she writes an herbal column. She also is a marketing expert in hospitality and the restaurant industry, a ceramist, and an avid outdoor enthusiast.

Resources

Chef Carlos Ramirez works his magic at Great Full Gardens in Reno. Photo by Chris Holloman

Building a strong culinary community

Member-based chef association offers much-needed support.

Reno-Tahoe-based chefs and restaurateurs can obtain support to not only survive but thrive from the American Culinary Federation High Sierra Chefs Association. Founded in 1976, the ACFHSCA provides health insurance as well as networking, mentoring, partnering, and fundraising opportunities that are developed from chefs’ needs and requests.

“We want to know what chefs would like to see,” says Fred Wright, treasurer of ACFHSCA, “whether that is a meat-cutting seminar or how to incorporate exotic herbs and spices. Or maybe our chefs want to see successful house plans or have a chance to win a scholarship to visit a culinary scene that is foreign to them. We are here to serve our members. More members mean a stronger community.”

ACFHSCA’s offerings, such as regular gatherings, aim to foster relationships, which can lead to jobs and provide a platform for sharing industry insights and bouncing new ideas off of fellow professionals. On the horizon, members are looking to develop an equipment rental system and raise more funds, which back scholarships for high school and college students and currently enrolled culinary students as well as cover costs of other endeavors, such as attending seminars or conferences or traveling to premier culinary destinations.

Wright, a certified executive chef and culinary arts instructor, oversees The Culinary and Hospitality Academy at the Academy of Arts, Careers and Technology in Reno. His students are usually only 14 years old when they begin with him, and within two years under his tutelage, they are qualified, trained professionals ready to work — and that is critical to expanding the number of qualified culinary workers in this community. Inspired by Wright’s investment in them, these young chefs understand the value of hard work.

“Owners can train an employee on just about everything but the right attitude,” Wright says. “I want my students to be passionate and find what makes them happy, and I try to get them there.”