Truckee chef serves in the wake of global disasters.

In early March, after days at sea, the Grand Princess cruise ship carrying thousands of passengers and crew, some sick with the coronavirus, docked at the Port of Oakland. Meanwhile, in a kitchen at the University of San Francisco, Truckee chef Elsa Corrigan and a slew of volunteers had already begun what would be weeks of work to produce three meals a day for those aboard the quarantined cruise liner.

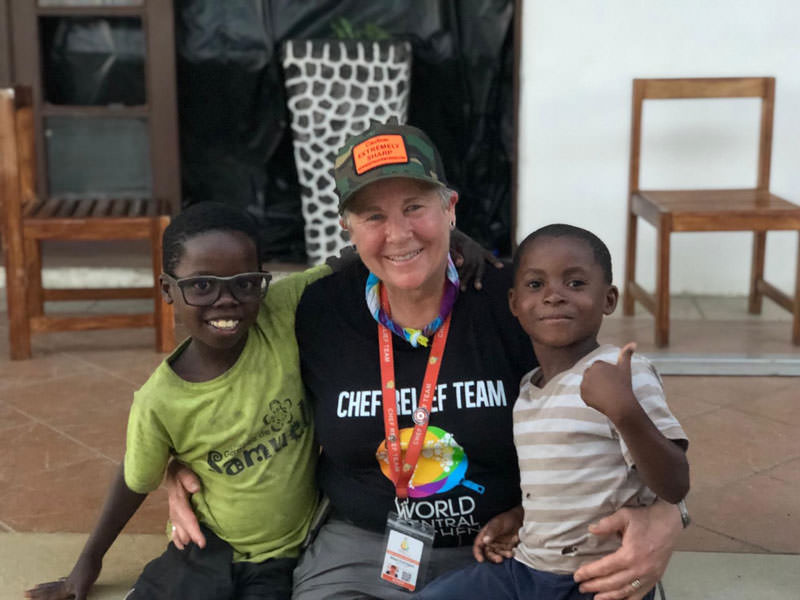

Since 2018, after deciding to close her restaurant, Mamasake, in The Village at Squaw Valley, Corrigan has volunteered for World Central Kitchen, a nonprofit organization dedicated to providing meals in the wake of disasters.

Founded in 2010 by celebrity chef José Andrés, World Central Kitchen started with programs aimed at finding solutions to poverty and hunger, including a clean-cookstoves initiative and culinary training programs. But in 2017, when Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico, the nonprofit mobilized and became “first food responders,” serving 3.7 million meals in the aftermath of the storm.

Since then, World Central Kitchen has served meals to displaced residents in California after numerous wildfires, been dispatched to Guatemala following the Fuego Volcano eruption, cooked in Indonesia after the earthquake and tsunamis, and provided sustenance in dozens of other locales around the globe.

“I liked the idea of a purpose other than working in the restaurant business,” Corrigan says. “I always wanted to be in the Peace Corps when I was a kid, but I wasn’t, so I found World Central Kitchen and pursued going to help them.”

Helping Others Help Themselves

Corrigan’s first mission was in Hawaii in May 2018, in response to the Kīlauea volcano eruption that forced 2,000 residents to evacuate.

“World Central Kitchen doesn’t want to just go in and save the day,” Corrigan explains. “They want to use us to help people help themselves. So to a certain degree we’re bringing our skills there and our systems, but we try to inject money into the community.”

The organization does this by paying to rent out kitchens that have been forced to close due to emergencies, hiring out-of-work staff, or using local food distribution companies that may not be getting the same amount of business.

While trained chefs and restaurant personnel run the kitchens, volunteers of all skill levels are put to work on everything from prep to packaging and delivery.

“We often have volunteers that come from the shelters because they want to help and be distracted, like in Hawaii,” Corrigan notes. “It was this slow-moving disaster. People were stressed out watching the progress of the lava field on TV all day, so they needed something to do, and they volunteered.”

In each emergency, the World Central Kitchen works with a nutritionist and locals to try and serve cuisine that will be familiar, comforting, and nutritious.

Difficult and Gratifying

Corrigan has traveled to Mozambique in Southeast Africa to feed evacuees as the country’s people grappled with an outbreak of cholera following a cyclone. She’s served Central American refugees in Tijuana seeking asylum in the United States and evacuees from several Northern California wildfires, including the Carr and Mendocino Complex fires. As bushfires devastated Australia, Corrigan flew to New South Wales to dispatch meals to small towns across the region.

“I’m used to cooking in chaos. In the ski area, all of a sudden you’re inundated with 100 people, so I was used to the pace of a disaster, and the distraction of it was good for me,” Corrigan explains. “You’re so busy trying to get it done, you’re thinking of the next 15 minutes. You’re not thinking about how sad or scary or dangerous it is. You’re thinking about how you can get the most food out to the most people.”

Though Corrigan is usually working long hours in the kitchen and not part of food deliveries to evacuees, she has seen devastation firsthand, such as in the Bahamas, when category 5 Hurricane Dorian left 70,000 people homeless.

“It was heart wrenching to see how destroyed everything was,” Corrigan recalls. “We’d give people some bottled water and a sandwich, and you could just see how thankful they were that somebody was caring for them when they felt lost and abandoned and the world’s come crashing down on them.”

Corrigan’s work with World Central Kitchen has been difficult and gratifying — just as she’d hoped. She’s met incredible chefs and volunteers, and she feels less helpless than she did watching on her TV as disasters unfolded around the world.

“I was fed up with the way the world is right now,” Corrigan says. “It can be stressful and fast-paced, but you meet the best people in disasters. Really what we want to do is comfort people at this tough time — to make them feel like they are respected and taken care of, and we do that through food.”

Claire McArthur is a freelance writer who is amazed and grateful for people such as Corrigan who step up in times of crisis. You can reach McArthur at Clairecudahy@gmail.com.

To volunteer for or donate to World Central Kitchen, visit Wck.org.