edible traditions

AW SHUCKS!

When the world was Northern Nevada’s oyster.

WRITTEN BY SHARON HONIG-BEAR

PHOTO COURTESY OF NEVADA HISTORICAL SOCIETY

In honor of this special edible travel issue, it’s the perfect time to honor a migrant that tops all others in sheer number: the humble oyster. How curious that this denizen of the sea found such popularity in this area, so far from America’s coasts.

Oysters not only tasted good. They also represented the good life. Champagne and oysters became the standard measure of success. In Virginia City’s boom years, stories abounded of streets paved with discarded oyster shells.

Oyster saloons

The coming of the railroad in the 1860s opened Reno up to the nation and made importing oysters easy. In the 1870s and 1880s, oyster saloons were everywhere, from Reno to Virginia City.

“This delicious article of food has become so necessary with every class of the population that scarcely a town in the whole country is without its regular supply. By means of railroads … [oysters] are carried to even the remotest parts of the U.S.,” said naval officer Lt. P. de Broca in his report back to French authorities regarding the state of the U.S. oyster industry.

In Reno, you could step off the Central Pacific and walk right into the station’s Depot Hotel, which featured the Lunch Room and Oyster Saloon. Oysters drew customers to the Reno Saddle Rock Oyster House, the Woodcock Restaurant and Chop House, and purveyors such as Berry & Novacovich. They were everywhere.

West Coast vs. East Coast

In the early years, oysters were brought by wagon over the Sierra. Small Olympia oysters from Washington, with their high brininess and sweet, coppery flavor, were the most common. The railroad opened up the market to different varieties, especially revered ones from the eastern U.S.

Restaurants capitalized on this, with statements such as this one in the Reno Evening Gazette in February 1884: “The Palace Restaurant is never caught napping. About 1,500 Eastern shell oysters arrived Saturday to accommodate its patrons and it is safe to wager that not an oyster will be left Tuesday …”

So began a long battle between oyster varieties. Eastern oysters were more prized, but Olympias were cheaper. An advertisement in the Nevada State Journal on Oct. 18, 1904, offered “large Eastern oysters 25¢ per dozen,” as opposed to purchasing 100 Olympias for 60 cents. Readers were assured that a shipment was delivered daily. The Popular Restaurant, located at 113 N. Virginia St., claimed in 1905 to be the “original” oyster house (no truth in advertising required!) with daily arrivals of fresh oysters.

Casino oyster bars

By the early 1900s, the craze for oysters died down. The opening of the Oyster Bar in New York’s Grand Central Station was heralded in the 1920s and ’30s — but with little impact on Reno. The Nevada State Journal in 1952 stated that “steak and chop houses, oyster bars … are not as numerous as they formerly were …”

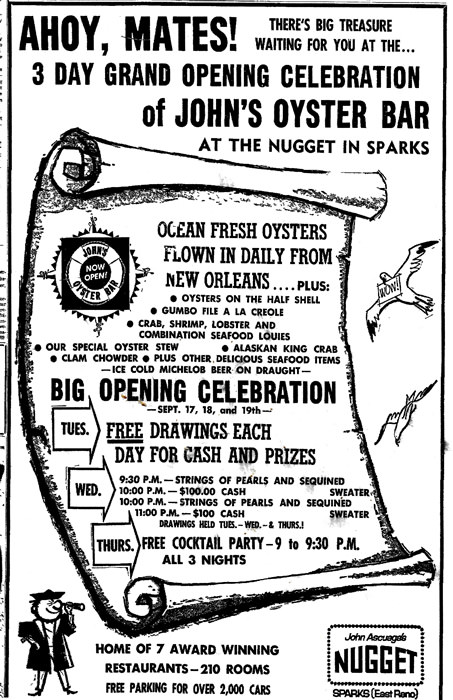

That changed in February 1963, when Big Joe’s Oyster Bar opened in the Thunderbird Hotel in Las Vegas. Within days of the restaurant opening, the management was forced to apologize publicly for running out of the shellfish. Reno eventually took notice, and John’s Oyster Bar, named for John Ascuaga at the Nugget Casino, opened in September 1963, “offering the best collection of seafood recipes from Alaska to Louisiana.”

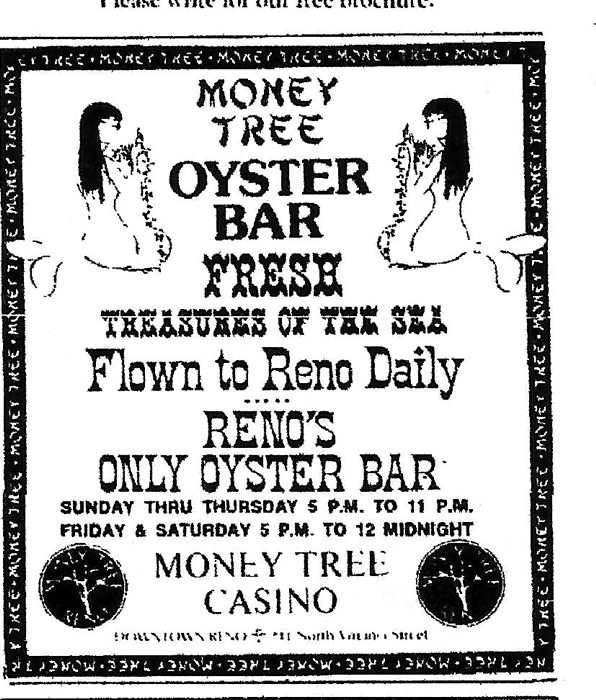

Despite the restaurant’s name, the menu was diversified, and oysters lost their exclusive place on the menu. Other eateries followed in Northern Nevada. The Money Tree Oyster Bar in Reno and the North Shore Club in Crystal Bay came along by 1974, and Harrah’s Reno opened the Seafare Restaurant and Oyster Bar in 1976. A number of casino oyster bars still carry on the tradition.

Times and food trends may change in Northern Nevada, but one thing seems clear: Oysters are here to stay.

Sharon Honig-Bear was the longtime restaurant writer for the Reno Gazette-Journal. She is a tour leader with Historic Reno Preservation Society and founder of the annual Reno Harvest of Homes Tour.