meet the rancher

a

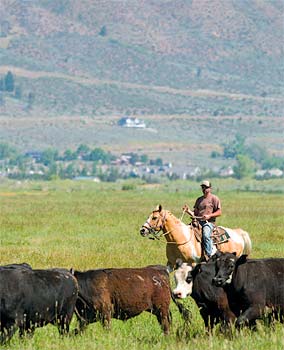

HOME on the RANGE

Running a cattle ranch is a hard life,

but some find it’s full of rewards.

WRITTEN BY BARBARA TWITCHELL

PHOTO BY DAVID CALVERT

A pencil holder, made from a distinctive part of a bull’s anatomy, stands on the corner of a rancher’s cluttered desk. The inscription on the base reads something like, “You need big ones to be a Nevada cattle rancher.” That sentiment is perhaps the one thing that any of the Silver State’s independent ranchers – whether big or small, pasture or feedlot advocate, conventional or grass-fed devotee – would wholeheartedly agree on.

Indeed, it’s a hard life, full of long days, backbreaking work, financial risk, and uncertain profit margins. The men and women who do it are a special breed themselves. Some say maybe even a dying breed. The reasons are many: diminishing natural resources, few processing plants in the west, and competition from mega cattle corporations, to name a few.

Still, there are those who persist in keeping the legacy of the family cattle ranch alive in this hardscrabble desert state. Some stick to the conventional ways, continuing to use the advances of genetics and technology to maximize productivity. Others are experimenting with alternative techniques, returning to the old ways of raising cattle on natural, grass-fed diets, hoping to appeal to the ecologically minded and health-conscious consumer. Different philosophies and practices, certainly, but they all have a shared goal of producing the best product they can while preserving the lifestyle they love.

THE LEGACY OF SNOOKS

“I’m a misfit,” Dave Stix says, laughing as he tries to explain how the son of Ivy League-educated parents – a New York art dealer and an artist – ended up as a cowboy.

He sits in the office of his sprawling Fernley ranch scanning scores of framed photos – family, friends, employees – that line every wall. They are photos that say as much about the man’s character as his history.

His family moved from New York to Reno when he was 10 and he says he knew immediately that ranching was the life for him. Bucking family tradition, he pursued his passion, learning his skills from local ranchers who took him under their wings and shared their knowledge. He proudly points to a small black and white photo.

“That was me at 12 with my first cow,” he says. “That’s how it started.” Today, he owns the 300-acre Dave Stix Livestock Ranch and also co-owns two hay farms and two commercial feedlots, including the largest in Nevada, with business partner Louis Damonte and their respective children. Stix practices the conventional form of ranching that has been the acceptable standard since the 1940s. Cattle are pasture or prairie raised for most of the first year of life, until they are weaned. Those that will be marketed for beef are brought to feedlots where they are fattened with grain. Standard practice is to implant a hormone pellet in the calf ’s ear at the feedlot in order to expedite and optimize weight gain. Antibiotics, he says, are administered only when medically necessary.

He brushes off concerns about hormones and antibiotics as if shooing away a bothersome fly, believing they are baseless and unproven. He quickly points out these practices have allowed cattle ranchers to provide the nation with a plentiful supply of nutritious, tasty beef at affordable prices.

“I think it’s a fallacy to say this is a problem,” Stix says, stating that there are strict USDA safety standards controlling these practices. “I think 99½ percent of all the cattle are real clean and handled perfectly in this country. Better than anywhere else in the world.”

He is not opposed to alternatives such as the grass-fed movement. But he views it as a fad, perhaps a good niche for small ranches. He does not feel that grass-fed beef can favorably compare with the look, taste, texture, and dollar value of conventionally raised, grain-fed beef.

Although most of his cattle are shipped out of state for sale and processing, Stix hand-selects some of his best cattle to provide the beef sold at European Food Emporium in Reno. All the cattle were born and raised here, fed locally grown grain, and were even processed here. From birth to the meat counter, they never leave Northern Nevada.

“I think that’s the biggest selling point,” he says. “The fact that they’re raised here, that’s way more important than whatever they’re eating. People know where it came from.”

And that connection is reassuring even to him. Despite the size of his ranch, he proudly states, “I know every cow, I know what cow she came from. And that cow in that picture – I would say that probably 90 percent of my cow herd, if you would do a DNA [test] on them, would trace back to her.”

He smiles somewhat sheepishly and adds, “Her name was Snooks.”

SIGN OF THE TIMES

It’s enough to elicit a quick double take and a chuckle from any passing motorist. A simple hand-lettered sign, posted in a roadside pasture in Pleasant Valley, just south of Reno, boasts: All of Our Cows Have Completed Anger Management Classes. And sure enough, the bovines grazing nearby all seem quite docile and content. And that’s just the way Jason Murry wants it. No mad cows here. Not even unhappy ones.

In this era of “mega-factory” ranches, where animals are generally shipped off to distant feedlots to be fattened and finished before processing, Murry shuns such practices in favor of what he calls a more natural, humane, almost hand-reared approach. The Murry Ranch cattle spend their entire lives in pastures, roaming freely. No wonder they’re happy. And they’re not the only ones. Spend five minutes with this man and it’s apparent – he loves what he does.

Although he grew up in Reno, Murry learned ranching at his grandfather’s Missouri farm, where he spent summers. He says he always knew that this is what he was meant to do.

“I love the animals,” he says, laughing. “I go out and sing to them!” A little embarrassed by the admission, he happily demonstrates how, in almost pet-like fashion, his cows come when he calls them.

Murry has been raising cattle his way at his Doyle, Calif., ranch and the Pleasant Valley pasture since 1996, producing meat that is free of hormones, steroids, and antibiotics. He raises both grass-finished and grain-finished cattle. Those that are grain-finished are fed specially formulated grain for the last 120 to 180 days, to enhance the meat’s flavor and texture. Those that are grass-finished remain on a 100 percent grass diet. The grass-finished beef then is dry-aged to tenderize it.

Murry sells his product the public in a manner that is gaining popularity among natural beef advocates. He sells the live calf to the customer. A brand inspector does the paperwork, transferring ownership (there can be split ownership for those who only want a half or quarter of a steer). Murry then takes care of all processing, using local USDAcertified facilities, where the meat is custom-cut and packaged according to the owner/customer’s personal specifications.

He has seen tremendous growth in consumer demand for natural beef. The trend toward grass-finished beef has been especially strong. He credits growing consumer awareness of the health benefits believed to be offered by grass-finished beef.

“The reason people call me is they’re very health conscious,” he says. “They like knowing where their meat came from; that it’s raised here; that it’s never had any chemicals in it, on it, or around it. That it’s stayed free from a feedlot situation.”

With demand growing, is he tempted to expand his operation? “Nah,” he says. “My wife and I feed them. The kids help sometimes. I don’t want to get any bigger because I like doing it myself.”

Does that include singing to the cows? He throws his head back and laughs, “Especially that!”

BACK TO THE FUTURE

There are two things you will get plenty of when you spend time with Lisa Lekumberry: local history and great beef jerky. And there’s good reason for both.

Roots run deep in these parts and no one knows that better than Lekumberry and her younger sisters, twins SheriWalters and Terri Billman. The women own Ranch One (also called Ranch No. 1) in Genoa and no land in Nevada has deeper roots than that. Ranch One was literally the first recorded land claim in 1852, in the territory that had yet to become our state. The sisters are the great-great-granddaughters of Robert Trimmer who purchased the ranch in 1909. Their family has continually raised cattle on that land ever since.

Originally, the ranch had been a self-sustaining farm. However, over time it had become a conventional cow-calf operation, breeding calves to be sold and shipped off to distant feedlots. It didn’t feel right to the sisters. About five years ago, they did some soul-searching, hoping to find a better way.

“It wasn’t so much a question of, Are we going to keep ranching?” Lekumberry says. “It was more, How can we sustain this? How can we reinvent it so that it can continue?”

She began to explore alternatives, setting the groundwork for change. The answer, it turned out, was as simple as reaching back to those deep roots.

Impressed by emerging scientific evidence of the benefits of 100 percent grass-fed beef, they decided that the way to a brighter future was to return to the old ways their family raised cattle for generations. Raising calves from birth to finish, no hormones or growth stimulants, no antibiotics except for infection, no grain – just 100 percent grassfed, pasture-raised beef. Beef like it used to be.

They had the advantages afforded by the lush green pastures of their beautiful 300-acre ranch, a superior line of cattle that goes back generations, and willing, supportive husbands. They also had enough grit and determination to make old Robert Trimmer proud.

Guided by scientific studies and traditional ranching wisdom, they spent years learning, experimenting, and improving their product. “It took a while, but we found just the right formula,” says J.B. Lekumberry, Lisa’s husband and marketing manager for their beef products. That formula involves an intricate balance of proper breeding, feeding, finishing, and, most importantly, providing a natural, stress-free existence for the cattle. “Our beef is leaner than conventional beef, richer in omega 3 fatty acids, free of chemicals. And that’s exactly what we’re trying to do: create a healthier product.”

Healthier, yes. But does it pass the palate test? Again they looked to their ancestors for answers, learning the old ways of dry aging to ensure a tender product. They also finish their calves solely on alfalfa for better taste. The result?

“It’s really good!” J.B. says. “We get great feedback from our customers.” They must be doing something right. Not only do they sell their beef through their own Genoa store, Trimmer Outpost, but it is also served in no less than seven local restaurants. As interest and demand grows, J.B. encourages neighboring ranchers to follow their lead.

“I think we’ve shown that if you put the effort back into it, you can bring back the old, natural way and the healthier beef it yielded,” J.B. says. “And there is a growing market for that.”

Lisa just nods and smiles while offering another sample of her homemade beef jerky. There’s marketing and then there’s marketing.

Barbara Twitchell is a Reno-based freelance writer. After many years working as a college administrator, she has returned to her own deep roots – writing – and she is loving it.