GUT GUIDES

Farmhouse Culture authors Kathryn Lukas and son Shane Peterson share their passion for the microbiome.

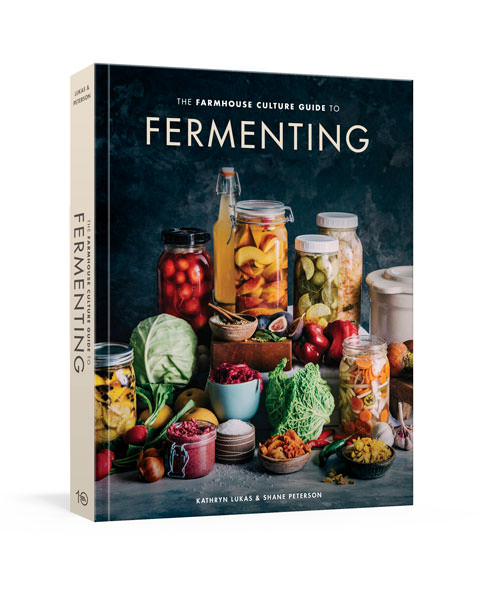

Kathryn Lukas, Reno resident and founder of the fermented food mega-brand Farmhouse Culture, and her son and fermentation expert Shane Peterson are the authors of the recently released The Farmhouse Culture Guide to Fermenting. Edible Reno-Tahoe writer Jamie Della got the opportunity to chat with these fermentation pros about how they got started and what tips they would offer to those interested in fermentation at home.

Why did you write your book The Farmhouse Culture Guide to Fermenting?

Lukas: When I started the business in 2008, my mission was twofold: to make our ferments accessible to as many people as possible and to get these healthy microbes into as many guts as possible. For me, that meant scaling the business in order to create affordable products and offering our community an opportunity to learn how to make our products with monthly classes. I felt strongly that demystifying the ancient craft of fermentation through an open-source approach would provide access for people who wanted to ferment at home and increase interest in our products. This book was a long time in coming and is an extension of these early goals.

How did you make your book user friendly?

Peterson: Through the years, we literally have made millions of pounds of ferments. Through trial and error, we learned best practices and methods for making consistently good products. For all of our recipes (which we call formulas for a reason), ingredients are provided in metric weights instead of volumes, which is important to achieving consistent results. With lactic acid fermentation, obtaining a precise salt percentage is the most exacting control, along with temperature, that the home fermenter can exert. Working with weights allows for a higher degree of accuracy, which equates to higher rates of success. We also provide sliding-scale fermentation “time and temperature” tables to help the home fermenter determine accuracy.

Why should people ferment at home?

Peterson: Fermentation is a way to preserve and enhance the flavor of the seasons. Empowered with a little knowledge and some basic equipment, such as a canning jar and a fermentation lid, the variety of fermented foods and drinks that can be made at home is more diverse than what’s available commercially. You won’t find fermented products at the grocery store, like most of the recipes we developed for our book: Mushroom Umami Sauce, Danish Remoulade, Smoky Tea Pickles, and Beet Horseradish Mustard, to name just a few.

What piques your interest today?

Lukas: We are fascinated by the synchronicity of the microbiome, the genetic material of all the microbes — bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and viruses — that live on and inside the human body. Microbes on the produce you select to ferment harmonize with the microbes from your hands, your kitchen, and the microbial environment in your home to create ferments that are unique. Every crock of kraut you make includes your personal microbial signature, a place-based family heirloom of sorts.

Jamie Della is the author of nine books that focus on seasonal lifestyle, plant ecology, and earth-based wisdom.

RESOURCES

The Farmhouse Culture Guide to Fermenting is available for purchase through Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and your local bookstore. $35

Taco Bar Mix

(reprinted with permission from The Farmhouse Culture Guide to Fermenting, text copyright 2019 by Kathryn Lukas and Shane Peterson. Photographs copyright 2019 by Eric Wolfinger. Published by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC. Makes ½ gallon)

970 milliliters distilled or spring water

30 grams unrefined sea salt

350 grams sliced carrots (¼-inch rounds)

350 grams sliced white radishes (¼-inch half-moons)

100 grams thinly sliced yellow onions

100 grams sliced green jalapeños (¼-inch rounds)

100 milliliters natural brine from our Basic Kraut recipe (also found in book) or from store-bought plain kraut

Equipment

Kitchen scale

½ gallon or 2-liter wide-mouth glass jar

Weight

Fermentation lid

Wash and sanitize fermentation equipment, including large bowl, knife, and cutting board, and set aside to air dry.

Make salt brine by bringing 300 milliliters of water to just under a boil in small saucepan. Remove from heat, add salt, and stir well until salt has dissolved. Add remaining 670 milliliters room temperature water to hot brine to cool down; set aside.

In large bowl, combine carrots, radishes, onions, and jalapeños. Mix with your hands until well combined. Transfer vegetables to jar. (Alternatively, you can layer each type of veggie in jar one by one, which produces a beautiful effect.)

Pour kraut brine into jar over vegetables. Pour salt brine into jar, leaving 2 inches of headspace.

Reserve extra salt brine in small jar in refrigerator to use as needed.

Place weight in jar on top of vegetables and press down until vegetables are completely submerged in brine. Seal jar with fermentation lid. Place sealed jar on plate or in bowl to catch any liquid displaced through the airlock during fermentation.

Ferment vegetables in a cool place away from direct sunlight (3 weeks at 64 degrees F is ideal — see the chart below). If, after the first 5 to 7 days, the level of brine drops below vegetables, add reserved brine as needed.

Taste vegetables after 2 weeks to determine whether flavor and sourness are to your liking. If they are not sour enough, reseal jar and let them ferment for another week, then taste again. When the mix is to your liking, replace fermentation lid with regular lid, seal, and store in refrigerator for up to 6 months.

Fermentation Temperature and Time

Above 68 degrees F: Ferment 2 weeks or less.

65 to 68 degrees F: Ferment 2 to 3 weeks.

64 degrees F: Ideal — ferment 3 weeks.

60 to 63 degrees F: Ferment 3 to 4 weeks.

Below 60 degrees F: Ferment 4 weeks or more.