edible travel

FOODIE FROLIC

Wining and dining along the Oregon Trail.

WRITTEN BY ST. JOHN FRIZELL

PHOTOS COURTESY OF HTTP://WWW.TRAVELOREGON.COM

AND HTTP://WWW.TRAVELPORTLAND.COM

Portland has captured the imagination of the food world for the past few years. It seems we have all caught Portland fever.

To say the city is food obsessed is both an understatement and a mischaracterization. Food, drink, and the enjoyment of such are as much a part of the fabric of this city as the Willamette River, which meanders through its center, and like that river, it’s nothing new. The surprise is that it’s taken the rest of the world this long to notice.

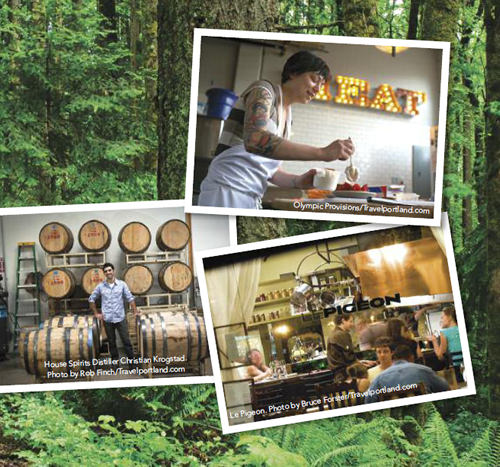

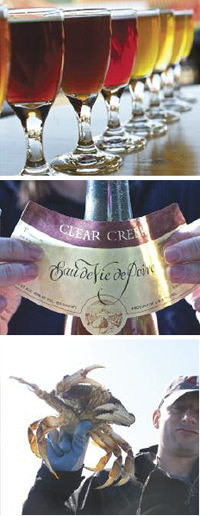

Food trucks? Portland has close to 700, with two or three new trucks opening every week. Locally made spirits? There are at least 11 distilleries in town, making everything from Aviation Gin to Eastside Ouzo. Craft beer? Please! They’ve called Oregon “Beervana” from way back. Coffee? Stumptown Coffee Roasters has redefined coffee culture. Plus salmon runs to die for, oysters and Dungeness crabs from the pristine coast, deep forests for foraging chanterelles and white truffles, and nine urban wineries bottling killer Pinot Noir. It’s no wonder that everyone has been jumping on the Oregon Trail, and giving Portland the kind of respect as a foodist destination that was once reserved for bigger cities such as San Francisco and Montreal.

Food Capital

While other great food cities might rely on their ethnic communities (such as Miami’s Calle Ocho) or age-old culinary traditions (such as New Orleans’ creole cooking), Portland’s status as a food capital is homegrown — it stems directly from its wealth of fresh, local ingredients. And eating locally isn’t just a fad there. It’s backed up by the law. In the early 1970s, Oregon created urban growth boundaries to protect farms and forests from encroaching sprawl. All this makes traveling through Oregon a little surreal — it’s as if the roadside strip mall hadn’t been invented.

“When people ask [if growth boundaries are] working, I say, ‘Drive between Portland and Salem,'” says Jim Johnson, a planner for the Oregon Department of Agriculture, on an online television show called Cooking Up a Story. “Where else can you drive an interstate freeway … and see nothing but farmland between major metropolitan areas, except Oregon?”

“When people ask [if growth boundaries are] working, I say, ‘Drive between Portland and Salem,'” says Jim Johnson, a planner for the Oregon Department of Agriculture, on an online television show called Cooking Up a Story. “Where else can you drive an interstate freeway … and see nothing but farmland between major metropolitan areas, except Oregon?”

The sheer proximity of abundant farms-to-tables in Portland is enough to turn any chef green with envy.

“We grow way, way more food than we can consume in this state,” Johnson says.

This makes eating local a no-brainer. The agriculture department calls the Willamette Valley “perhaps the most diverse agricultural region on earth,” and thanks to the mild winters, fresh produce abounds year round — and not just on elite, effete menus. At Community Plate in McMinnville, Ore., chef Jesse Kincheloe estimates 80 percent to 85 percent of his Americana menu’s ingredients are grown nearby, right down to the Tillamook Cheddar in his mac and cheese, the Oregon albacore in his dynamite tuna melt, and the hazelnuts ground into milk for your coffee. All over Portland, chefs use local ingredients to make standard dishes superior, such as chef Tommy Habetz’s unforgettable house-made sausage, egg, and cheese on a poppy seed roll at Bunk Sandwiches, or the instantly addictive carbonara served at Riffle NW, where local squid stands in for spaghetti.

Wine Success

The Willamette Valley — with its rich, alluvial soil and warm, dry summers — has been compared to another notable growing region: Burgundy, France. That’s because winemakers in the Willamette have had great success growing Pinot Noir, the grape considered the Holy Grail of winemaking — famously difficult to grow, and even harder to make into good wine.

“You can’t mess with Pinot. It remembers in the bottle. It’s like an angry teenager,” says Ellen Brittan, general manager of The Carlton Winemakers Studio, a co-op winemaking facility in the heart of Oregon’s wine country. An industrial-chic wonder of green engineering, utility and good design, the Studio is home to 10 different winemakers who source grapes from nearby vineyards and make wine, from crush to bottle, at the shared facility. For these vintners, winemaking is a collective act; they’ve come together to share equipment, but naturally end up sharing ideas and opinions in the process.

For one of the winemakers, Joe Pedicini, that sense of community defines the Oregon food and wine scene at least as much as its natural bounty, and has for at least a generation. Pedicini has been “fascinated with fermentation” since he was boy, watching his Italian grandfather fill wine barrels in the basement of their suburban New Jersey home. But it wasn’t until he moved to Oregon in 1993 — for a job at Deschutes Brewery, then at the cutting edge of Oregon’s still-booming craft beer movement — that he found lots of like-minded people, fascinated by the things they ate and drank.

I came to town expecting every café to pour coffee from Stumptown. But while that bean business was busy taking Manhattan, dozens of microroasteries bloomed in the Rose City — Ristretto, Coava, and Courier, to name a few — many of which will deliver to your house via bicycle.

Portland Lifestyle

Most New York transplants, such as chef Gregory Gourdet, find the Portland lifestyle to be a welcome breath of fresh, Douglas fir-scented mountain air. Gourdet worked his way up to chef de cuisine at 66, Jean-Georges Vongerichten’s now defunct Shanghai-inspired restaurant in TriBeCa, but his Manhattan lifestyle took a toll.

“I was staying out too late partying, getting chewed up and rundown. I was ready for a change,” Gourdet says. Now he’s traded late nights on the town for early mornings in Portland’s Forest Park, the sprawling, thickly wooded reserve to the west of Portland’s center, where he’s trained for eight marathons. But he kept what Jean-Georges gave him: a love for contemporary Asian cuisine, which he puts to use at Departure, a swank, cosmopolitan affair on the roof of The Nines hotel, in dishes such as roasted mushrooms with wild ginger and spruce.

Since arriving in Oregon, he’s been rummaging through the spectacular natural pantry of the Northwest, exploring the wide range of ingredients that define the region’s cuisine. Early in Gourdet’s tenure at Departure, his friend Ben Jacobsen (of Jacobsen Salt Co.) brought the chef bundles of wild greens that he had gathered near Netarts Bay while filling his buckets of seawater.

Gourdet doesn’t look like your typical forager; he has a relaxed mohawk (he’s a hair model for a hip salon in town) and wears the kind of oversized frames favored by both chef Mark Ladner of Del Posto Ristorante in New York City and the late actor Charles Nelson Reilly. For Gourdet, this kind of intimate relationship with the earth and sea is new, despite his experience cooking in some of Manhattan’s top kitchens.

Culinary Incubator

What draws people to Oregon is something different — less the desire to stand apart than to come together. Late on a Friday night, I knock on the window of KitchenCru, a culinary incubator on the edge of the Pearl, Portland’s fashionable shopping district. Like Portland’s progressive collective wineries, KitchenCru is a shared space; its slick, spacious kitchen, filled with expensive equipment, can be rented by small food companies by the hour, and its management helps new businesses get off the ground.

As the Pearl’s restaurants overflow with giddy summer Friday crowds, a handful of industrious entrepreneurs are busy making the food that’ll get Portland through its weekend. In one corner, bakers are proofing dough for the bagels that’ll be served tomorrow at Bowery Bagels, just across the street, and owned by KitchenCru founder Michael Madigan. Across the room, Sara Suffriti rolls out crust for the pies she sells under her brand Pieku. Around the corner, Aaron Silverman finishes a batch of fresh pork sausage that he’ll sell under his label, Tails & Trotters — soon he hopes to be able to legally sell his Northwest prosciutto, made from pigs finished on a diet of Oregon hazelnuts. Though it’s a business incubator, KitchenCru feels as downright socialistic as Portland itself, a lefty workaround to the traditional capitalistic system. Despite the hour, there’s a sense of jolly camaraderie in the air, where everyone seems to know one another, and the kitchen hums like a beehive. It’s that buzz, that energy that Joe Pedicini felt when he first moved to Oregon, where everyone knew they had such potential — Joe’s dream of the ’90s is alive in Portland.

When not writing or shaking drinks at Fort Defiance (his restaurant in Red Hook, Brooklyn), St. John Frizell browses the real estate section of The Oregonian.

A longer version of this story first ran in the fall 2012 edition of Edible Manhattan.

Resources

Portland Beer information

http://www.Portlandbeer.org and http://www.Portlandbeer.org/breweries/map/

Portland distilleries

http://www.Distilleryrowpdx.com

Willamette Valley wines

http://www.Willamettewines.com/winery-map/

Stumptown Coffee Roasters

http://www.Stumptowncoffee.com/location/division/

Food trucks and carts

http://www.Foodcartsportland.com

http://www.Saveur.com/article/travels/guide-portland-food-trucks

Community Plate in McMinnville, Ore.

Tillamook cheese

Hazelnuts

http://www.Oregonhazelnuts.org/growers-corner/hazelnut-nurseries/

Bunk Sandwiches

Riffle NW

Le Pigeon

Departure at The Nines hotel

http://www.Departureportland.com

KitchenCru

Pieku

http://www.Facebook.com/piekupie

Tails & Trotters

http://www.Tailsandtrotters.com

Bowery Bagels

Jacobsen Salt Co.

Carlton Winemakers Studio

http://www.Winemakersstudio.com

Travel information