edible traditions

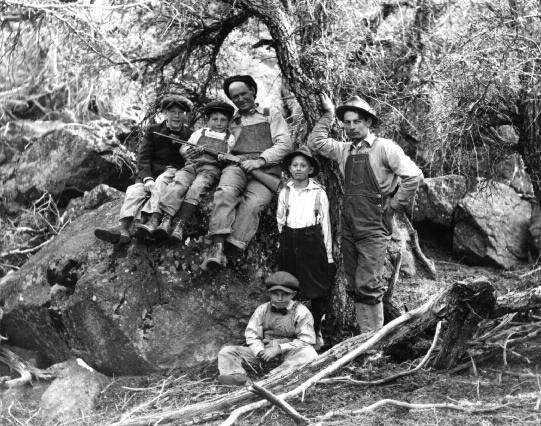

Paiute woman drying fish, circa 1906-1922

DINING IN SEASON

Prior to modern food storage,

preserves were king in winter.

WRITTEN BY JEN HUNTLEY

PHOTO COURTESY OF SPECIAL COLLECTIONS DEPT,

UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA, RENO LIBRARY

Chilean grapes in winter, asparagus in the fall — we are so accustomed to all produce, all year long, that food’s seasonal aspect is merely a charming nostalgia to most of us. And while many of us are shifting to more local, seasonal produce, we frequently lose momentum in the face of winter’s slim pickings.

Chilean grapes in winter, asparagus in the fall — we are so accustomed to all produce, all year long, that food’s seasonal aspect is merely a charming nostalgia to most of us. And while many of us are shifting to more local, seasonal produce, we frequently lose momentum in the face of winter’s slim pickings.

After all, what did people do before the advent of refrigerators, international transportation networks, and computer-operated greenhouses? What was the culinary experience of the seasonal cycle? How did Nevadans prepare for the cold winters?

Native Nevadans had two main strategies: seasonal migration and dehydrating food. The first allowed them to harvest the foods that came available at different times of the year — pine nuts in the fall, fiddleheads in the spring. By drying meat and fruits, tribal people could capture the surplus of every season and either transport it or cache it for lean times.

Similarly, Euro-Americans brought traditions, expertise, technology, and plants and animals that allowed them to adapt to the seasonal cycle by preserving the surplus of summer and fall for consumption in winter and early spring. Coincidentally, Ball canning jars were invented the same year as the first mining in Virginia City: 1858. Prior to the advent of electricity, cellars provided cool storage for many fruits and vegetables.

Winter was the season of meat in the northern hemisphere, because the cold temperatures kept it fresh. Indeed, many of our fondest holidays began as pagan rituals to coincide with the slaughter and feast of meat: “Fat Tuesday” and its Carnival derive from the last days to consume flesh before the early spring and its limited diet of dried legumes (or lentils).

But Nevada miners had a hunger for wildly exotic foods; archaeological digs of mining towns and cities turn up countless oyster shells and Champagne bottles, some of which were transported hundreds of miles over outrageously hostile terrain. One symbol of the lucky strike, exotic and out-of-season food remains an expression of wealth that also speaks to our unconscious fears of dependency on the fickle environment. Our modern industrial food system elaborates these tendencies. But as more and more of us reconnect with our local farms, or grow and preserve our own food, we re-learn those seasonal rhythms of eating, yes, even in winter. Everything old is made new again.

Jen A. Huntley is an independent scholar, writer, and consultant on educational excellence and sustainable communities.